For 10 weeks of this summer I volunteered in the rural village of Santa Marta, department of Cabañas, in the north-east of the smallest country in the region, El Salvador. My time there was characterised by the exuberance and enthusiasm of the Salvadoran people and through my continuous improvements in both listening to and speaking Spanish, I was better able to understand the story of the tiny pueblo and its people high in the humid, forest covered mountains of Central America.

For nine of those 10 weeks, I stayed in a host home with Paulina Beltrán, her daughter Beatrice, and two young girls Alejandra and Marisol. It was in this household that I and co-volunteer Alfred learnt the story of one of the most inspirational and selflessly generous people I have ever met. Not only did Paulina exude the most unwaveringly happy and positive demeanour at all times, but she was also both incredibly thoughtful and utterly genuine. Although her physical resources were minimal, emotionally she had a seemingly inexhaustible reserve of laughter and energy that made a mockery of her fifty-one years.

Paulina would be up and singing her personally crafted melodies by 5am most mornings, a habit that was at times resented by Alfred and I, but one that we never truly had the heart to discourage. The first rays of sunlight into our room would be noisily raced by Paulina, loudly snapping open the huge iron door and demanding to know whether or not we had slept well, without accepting a sleepy grumble as a valid reply. She then took great pleasure in bustling into our room around four to five times over the next couple of hours or so, offering guineos, guayabas, manzanas and nonas “to help keep you strong and healthy, because you are going to work very hard today, aren’t you?”

We would rarely see her during the working day, unless we passed by the stream where she would tirelessly scrub our clothes or occasionally in those late, sweltering afternoons when she visited Sensuntepece on the communal bus and could be seen hanging out of the window waving, shouting, and beaming at us, as it passed by our worksite. In the evenings, returning to the house covered in red dirt, paint, and cement dust, we would often receive further gifts in the form of pan dulce (sweet bread) and charramuscas (frozen chocolate) from a woman who seemed to stop at no length in making sure we never got close to going hungry under her roof.

You don’t expect this sort of generosity from most people, and certainly not from people who harbour as troubled a personal history as Paulina.

For much of the 1970s, Santa Marta was not exempt from the cruel hand of the Salvadoran military forces, which embarked on a vicious tour of repression against its people. It murdered priests, raped pregnant women, massacred livestock, and destroyed crops in an attempt to annihilate the left-wing guerrillas of the FMLN in the ‘Scorched Earth’ campaign, aimed at rural towns and villages. They wanted to “sacar el pes del agua”, in English, “remove the fish from the water”.

In 1981, the unarmed civilian inhabitants of Santa Marta, Paulina included, were forced to flee their homes taking only what they could carry in order to escape the wave of fiery extermination. Paulina has mentioned the events of those terrifying days on several occasions, but only once or twice did she muster the resolve to recount the story in depth and in each case her words were cut short by the creasing of her deeply expressive features into uncontrollable sobs. She talked briefly of the running, the screaming, of holding a child tightly to her chest as helicopters flung bombs down on either side, and of her frantic passage across the treacherous Rio Lempa, as members of both the Salvadoran and Honduran armed forces stationed on the hills above aimed weapons down at the seething mass of human fear below.

Witnessing that massacre was torture to endure.

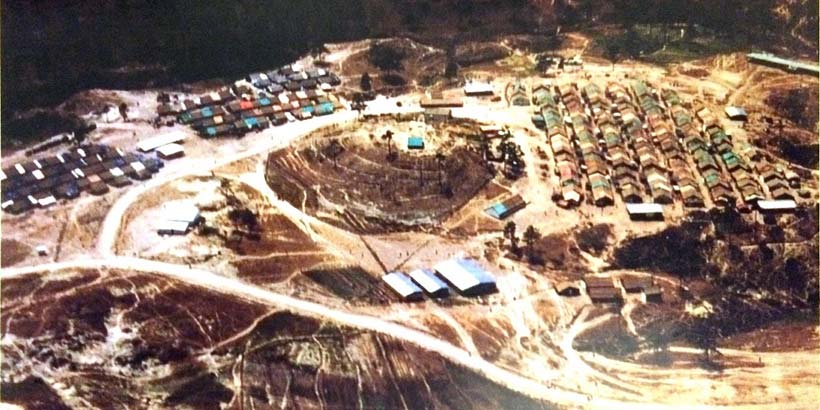

The next six years of Paulina’s life passed within the confines of a UN sponsored Refugee Camp in La Mesa Grande, a settlement from which none were allowed to leave and those that did would almost certainly be killed. It was in 1987 that one thousand and eight former inhabitants of Santa Marta made the extraordinary decision to return to their former home, a village in which only one building remained.

Paulina chats proudly of her role in the rebuilding of a society, the countless hard days spent flattening out maize for pupusas, collecting water from the river, caring for children without rest, demonstrating the resolve and identity of a strong-willed people. She is well-known throughout the village as one of those who refused to succumb to the darkness of memory and continues to flourish in the aftermath of the horrors of ‘La Guerra’ and its suffocating repression. Her history is wrought with unimaginable terrors and her perceptions of life have been irrevocably altered so it’s strange to think that the relatively safe environment of post-war Santa Marta is the only one in which I will ever see her.

It’s incredible that my overriding memory of this wonderful woman that has suffered so much will be one of her excitedly hopping on one leg demonstrating her favourite dance move, bandana round head, charmingly toothless, but with a huge grin filling her mouth and eyes. She has seen some terrible things. She has kept many of those things to herself. But she has never, ever, given up her right to laugh and to express herself freely without caring for the judgement of others.

In my memory she dances on, revelling in her ability to make others smile. In hers, she tries to lock away the torment that she may never truly be able to. But she doesn’t let it show.

She is an inspirational woman.

Written by ICS Alumni Jack Greenwood (July - September 2015 cycle) especially for the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women 2015

Paulina Beltrán – Una sonrisa imparable

Este verano, por diez semanas, fui voluntario en un pueblo rural llamado Santa Marta, en el Departamento de Cabañas, ubicado en el noreste del país más pequeño de la región, El Salvador. Mi tiempo allá fue marcado por la exuberante y animada gente salvadoreña, así como por el constante desarrollo de mi español (hablado y escrito), que me permitió comprehender mejor la historia de este pequeño pueblo y de su gente, ubicado en una zona alta y húmida de las montañas de Centro América.

Durante nueve de esas diez semanas me quedé alojado en la casa de Paulina Beltrán, quien vive con su hija Beatrice, y sus dos nietas Alejandra y Marisol. Fue en esta casa que yo y mi compañero de habitación, también el voluntario británico, Alfred, aprendimos la historia de una de las más inspiradoras y generosas personas que alguna vez he conocido. Paulina no solo mantenía una postura continuamente feliz y positiva, si no también era considerada y verdaderamente genuina. A pesar que sus recursos financieros eran escasos, emocionalmente Paulina tenía una reserva inagotable de risa y energía, la cual parecía hacer burla de sus 51 años.

Cuando se despertaba, casi todos los días a las cinco de la mañana, Paulina de inmediato empezaba a cantar sus propias melodías. Esta costumbre era algunas veces resentida por Alfred y por mí, pero en la realidad nunca tuvimos el corazón para decirle. Los primeros rayos de sol en nuestra habitación eran acompañados por las melodías de Paulina, quien abría con tremendo ruido la enorme puerta de metal de nuestra habitación y demandaba saber si habíamos o no dormido bien, sin nunca aceptar nuestros gruñidos como válidas respuestas. Le daba enorme placer entrar por nuestra habitación como cuatro o cinco veces durante las horas siguientes, para ofrecernos guineos, guayabas, manzanas y anonas, para según ella “ayudarnos a mantenernos fuertes y saludables, porque ustedes van a trabajar duro hoy, ¿verdad?”

Raramente la veíamos durante las horas laborales, a no ser que pasáramos por la orilla del río, donde Paulina lavaba sin descanso nuestras ropas, u ocasionalmente en esas tardes sofocantes, cuando ella visitaba Sensuntepeque en el bus comunitario, y la veíamos colgando de la ventana con su mano en el aire, o gritándonos radiante cuando pasaba por el lugar donde estábamos trabajando. Por las noches, cuando regresábamos a la casa cubiertos de polvo rojo, tinta, y polvo de cemento, nos reciba con más regalos - pan dulce y charramuscas - esta mujer parecía querer que mientras estuviéramos en su casa jamás pasáramos hambre.

Uno no se esperaría este tipo de generosidad de la mayoría de la gente, y ciertamente no se esperaría de una persona con un pasado tan difícil como el de la historia personal de Paulina.

En gran parte de los años 70, Santa Marta no pudo escapar a la mano cruel de las fuerzas militares salvadoreñas, quienes iniciaron una cruel gira de represión contra sus habitantes. Mataron a padres, violaron a mujeres embarazadas, masacraron el ganado, y destruirán los cultivos a manera de aniquilar las güerillas de izquierda del FMLN en su campaña de “Tierra Arrasada”, dirigida a los pueblos rurales. Según ellos, querían “sacar el pez del agua.”

En 1981, los habitantes desarmados de Santa Marta, Paulina incluida, fueron forzados a huir de sus casas llevando solo lo que podían cargar, para poder escapar de la tremenda ola de exterminio. En raras ocasiones, Paulina mencionó esos acontecimientos, pero solo una o dos veces reunió las fuerzas para contarnos esa historia con más detalle, y cada una de sus palabras eran interrumpidas por sus lágrimas y llanto. Habló brevemente sobre la marcha, los gritos, o tener que sostener firmemente contra su pecho a su hija, mientras los helicópteros lanzaban bombas cerca de ella, y sobre el frenético cruce del traicionero Rio Lempa, mientras los miembros de las fuerzas armadas Hondureñas y Salvadoreñas, que estaban en los montes, desde arriba apuntaban sus armas a la hirviente masa de miedo humano que estaba debajo de ellos.

Ser testigo de la masacre era una tortura difícil de soportar.

Los seis años siguientes de la vida de Paulina pasaron en un campo de refugiados de las Naciones Unidas, en Mesa Grande. No les era permitido salir y si lo intentasen ciertamente serian asesinados. Solo en 1987, los 1008 habitantes de Santa Marta tomaron la extraordinaria decisión de volver a sus casas, a su pueblo, donde solo un único edificio quedaba intacto.

Paulina menciona orgullosamente su rol en la reconstrucción de esa comunidad, en los innumerables y arduos días que pasaba moliendo el maíz para hacer pupusas, recolectando agua del rio, cuidando de niños y niñas sin reposo, mostrando así la tremenda determinación e identidad de la gente decidida a sacar adelante sus vidas. Ella es muy conocida en su pueblo como una de las personas que trata de no sucumbir a la oscuridad de la memoria. Paulina continúa floreciendo a pesar de las secuelas y horrores de “La Guerra” y de su sofocante represión. Su historia personal esta forjada de inimaginables horrores y su percepción sobre la vida ha sido irrevocablemente alterada. Por lo tanto me es extraño imaginarla fuera del relativo ambiente seguro de Santa Marta.

Es increíble que mi principal recuerdo de esta maravillosa mujer que tanto sufrió, sea verla saltando en una pierna mostrándonos su paso favorito de baile con un pañuelo en la cabeza, encantadoramente desdentada, pero con una enorme sonrisa que llenan su boca y sus ojos. Ella fue testigo de escenas terribles y las guarda con ella. Pero Paulina nunca renunció a su derecho de reírse y de expresarse libremente sin preocuparse por el juicio de los demás.

En mi memoria, Paulina sigue bailando, deleitándose en su capacidad de hacer a los demás sonreír. Intentando así ocultar el tormento de su pasado, algo que creo que jamás logrará hacer. Pero nunca lo muestra a nadie.

Paulina es una mujer inspiradora.

Escrito por el voluntario de ICS Jack Greenwood (ciclo de Julio - Septiembre) especialmente para el Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Violencia contra la Mujer